House of Bacchus and Ariadne (Maison de Bacchus et Ariane)

Province

Africa Proconsularis

Africa proconsularis (Pleiades)

Province Description

The history of Roman Africa begins in 146 BC with the destruction of Carthage and the establishment of the province of Africa in the most fertile part of the Carthaginian Empire. The new province covered about 5000 square miles (17,172 square kilometers) of the northern part of modern Tunisia. A praetor governed the area from his headquarters at Utica. The Romans inherited a thriving agriculture developed by the Carthaginians. The climate was hospitable. Wheat and barley were the most important cereals; wine and olive oil were also produced and there were various fruit trees.

Location

THUBURBO MAIUS (Henchir Kasbat), Tunisia

THUBURBO MAIUS (Henchir Kasbat), Tunisia (Pleiades)

Plan of Thuburbo Maius (CMT, Thuburbo Majus)

Location Description

The city occupies the slopes of a hill in a fertile grain producing area about 50 kilometers to the south of Tunis. Originally a settlement of mercenary soldiers after the fall of Carthage, it was raised to a municipium by Hadrian (117-138), and to a colony during the rein of Commodus (177-192). The chief public buildings and the most beautiful homes date from this period. After the crisis of the Empire during the third century, Thuburbo saw a rebirth in the fourth century; but as imperial authority declined the city became a mere village.

Garden

House of Bacchus and Ariadne (Maison de Bacchus et Ariane)

Keywords

- domus

- peristyle houses

- mosaics (visual works)

- triclinia (rooms)

- basins (vessels)

- root cavities

- pipes (conduits)

- pools (bodies of water)

- fountains

- pits

- furniture

Garden Description

This large house, occupying most of an insula (excavated in l925), dates in its present form from the early fifth century. The SW part of the house was devoted to business, the production of olive oil.

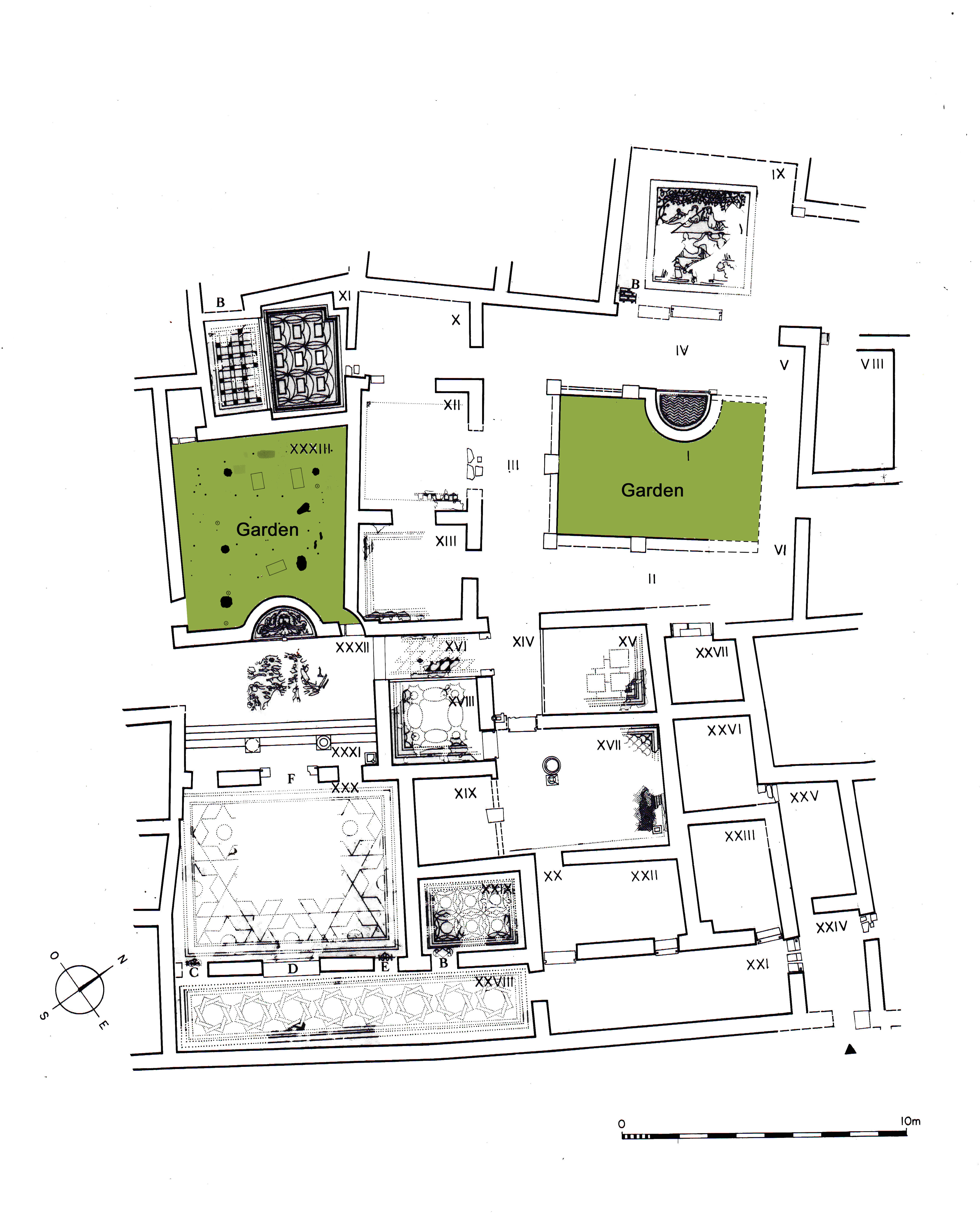

The rooms on the NE side of the residence area were arranged around a peristyle garden. The mosaic of Bacchus and Ariadne in the large room opening off of the NW portico gave the house its name. The bottom of the semicircular basin projecting into the garden opposite this room was decorated with a wavy water motif; the interior was decorated with plants and imitation marble. This part of the house would have been used by the family and the rooms on the SW for more personal purposes (Plan view, Fig.1). Preliminary excavations in this garden revealed a row of cavities along the southern edge of the garden. Roots arranged in a straight row suggest a produce garden.

The courtyard garden, opposite the triclinium, was located three steps below the triclinium. The triclinium had a view on the garden, framed by two columns. The semicircular mosaic pool (2.20 m in diameter, 1.10 m deep), which projected into the garden, was decorated on the bottom with the head of Oceanus. A pipe indicated where a fountain had jetted from his mouth.

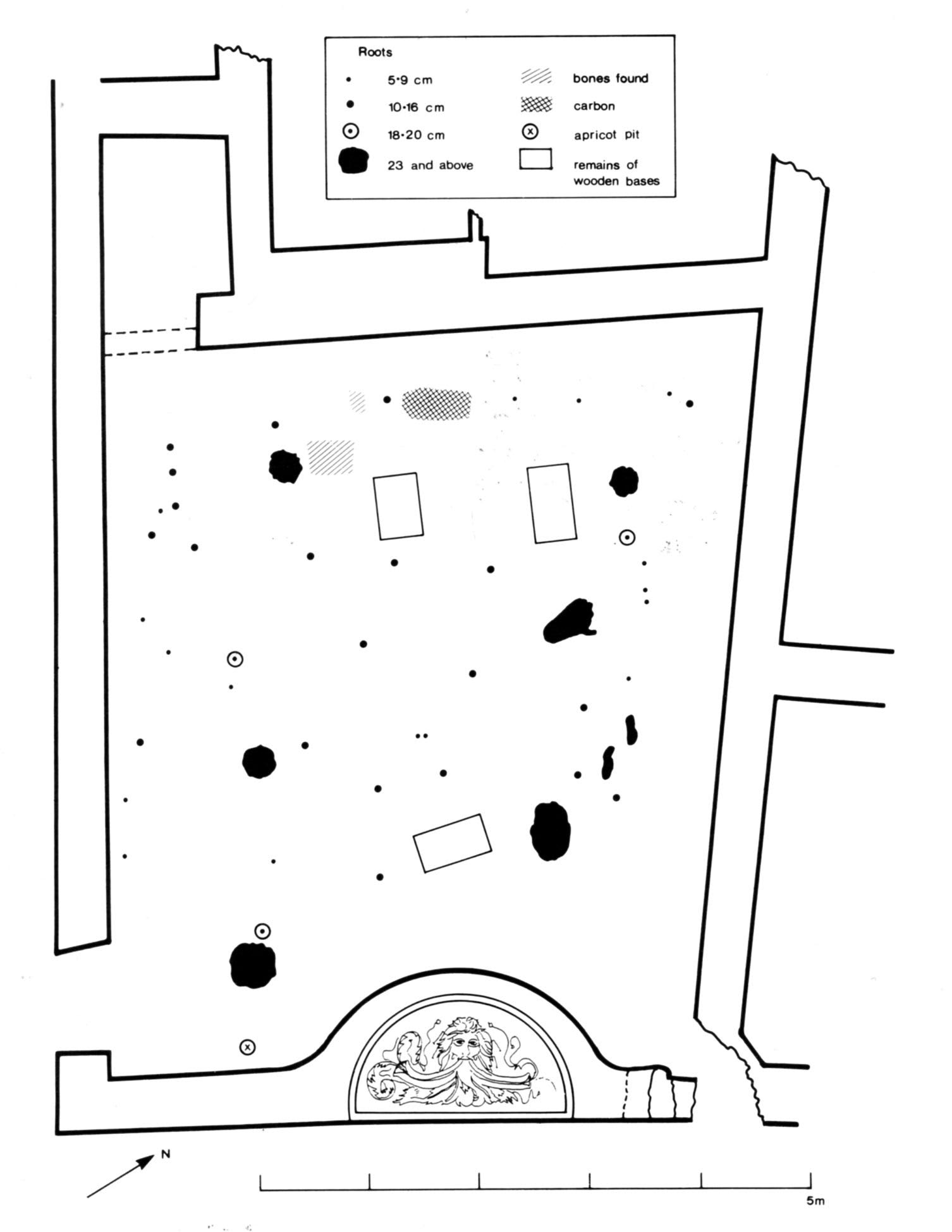

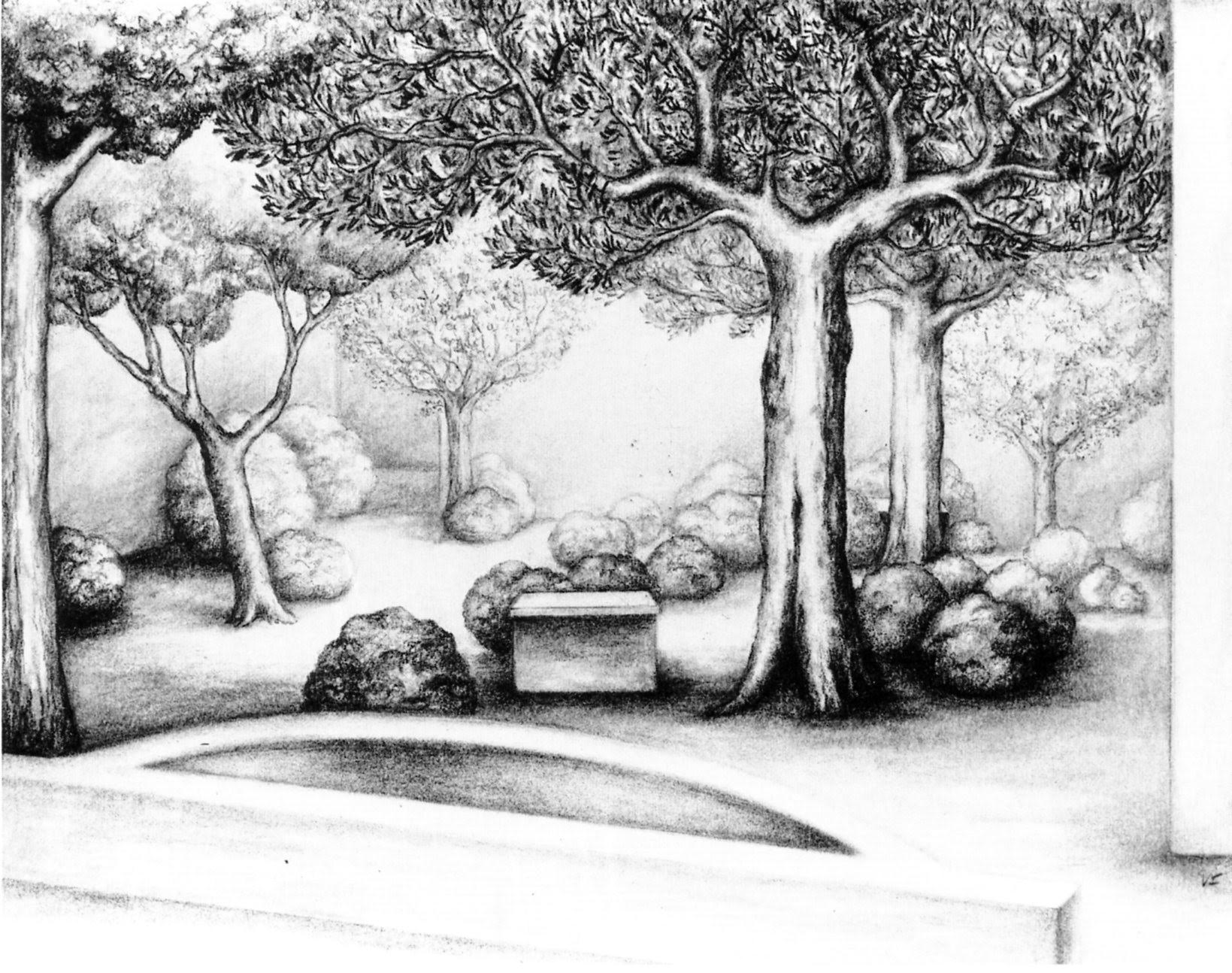

When the 25-30 cm of soil that had accumulated through the centuries, probably transplanted by the wind, was removed in 1990, evidence of the plantings at the last occupation level was perfectly preserved. The soil that formed when the roots decayed was of an entirely different texture and color from that of the surrounding soil (Fig. 2), making the shape of the ancient roots at ground level as distinct as those of lapilli-filled cavities in the Vesuvian area. There were six large tree-root cavities, the largest dimension at ground level 30-50 cm in diameter, three smaller tree root cavities 18-20 cm in diameter, and many smaller cavities most of which were 5-10 cm in diameter (Fig. 3). Three large rectangular areas, approximately the same size (36 x 72 cm, 40 x 60 cm and 46 x 63 cm) and only a few cm deep, represented decayed wood, the two in the rear garden were probably the wooden bases of a garden bench or table. The one in the back of the mosaic fountain in full view of the triclinium perhaps supported a small table (Fig. 4).

Numerous olive pits and bones that showed evidence of burning were found in an area (ca 32 x 45 cm) near the rear of the garden, some on the surface, some shallowly buried. Nearby, in a place where there had been frequent fires, were more shallowly buried bones. Of the 34 bones found, five were those of pig (Sus scrofa L), eight were of sheep (Ovis aries L.) or domestic goat (Capra hirca L.), one was from a rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.), and one from a carnivore (cf. Felis catus L.), probably a pet cat. The other bones were too badly broken to be identifiable. An apricot pit was found near the large tree-root cavity in the south corner of the garden.

The location of the cooking area behind the bench or table is logical. Homes at Thuburbo had no kitchens, and cooking was done in the garden. Servants would have cooked the food at the rear of the garden, using the table or bench (which was screened by plantings) for both supplies and cooking food, preparatory to serving guests in the formal triclinium. At other times, during the hot summer the family, and perhaps a few special guests, enjoyed meals in the garden. When the accumulated bones became a problem, they were raked into the fire, and those not burned were shallowly buried, as was the common Roman practice.

The gardens in Tunisia were not preserved at an exact moment in history, as were those in the Vesuvian area. The trees and shrubs in Tunisian gardens would have continued to grow for some time after the site was abandoned. What was uncovered in 1990 was not the garden at its prime. Some of the smaller roots may have been those of seedlings that grew from unpicked fruit that fell from the trees.

The trees in this garden were probably food bearing trees. Ancient Tunisia had few other trees. They knew the palm, pine and cypress, but these trees would have been overpowering in such a small garden. The two large tree-root cavities (on the right in Fig. 3) are the proper size and shape for olive trees. The middle tree on the left was perhaps a fig tree; the tree in the south corner of the garden may have been an apricot. The smaller trees were probably fruit or nut trees. The ancient Tunisians knew the quince, pomegranate, plum, citron, peach, apple, pear and grape – all pictured in the mosaics. There may also have been a few grapes raised for table use in this garden.

We next consider the identity of the many smaller roots. Since this garden was viewed from the large formal dining room, an effort would have been made to make it beautiful all year round. Fruit trees would have been beautiful in flower or fruit but they are deciduous. Only the olive tree is evergreen. Ornamental plant material in ancient Roman gardens was extremely limited, but the majority of the plants were evergreen and produced beautiful gardens in every season, welcome in winter and refreshingly cool in summer. The plant material in Tunisia was limited for the most part to the laurel, myrtle, rosemary, laurustinus, oleander, acanthus and ivy. There does not seem to be a place in this garden for ivy, but any of the other plants could have been used. Roman gardens had few flowers, especially with color. Roses are pictured in Tunisian mosaics and they may have been used in this garden. The oleander (Nerium oleander L.) with its striking pink flowers is the only colorful garden shrub. It is widespread in all Tunisia and tolerant of variable growing conditions. It seems probable that oleanders, so prominent in modern Tunisian gardens, as well as in the wild, also added color to this garden.

Maps

Plans

Fig. 1: Plan of the House of Bacchus and Ariadne. (CMT, V. II, fasc.4, Pl. XXIV. Jashemski, W. F., 1995, p. 561, fig. 2)

Images

Fig. 2: Decayed tree root 23 cm in diameter. (Photo J. Foss, Jashemski, W. F., 1995, fig. 5)

Fig. 3: Detail, Plan of courtyard garden, House of Bacchus and Ariadne. (Victoria I, Jashemski, W. F., 1995, fig. 7)

Fig. 4: Reconstruction of plantings in courtyard garden of House of Bacchus and Ariadne. (Victoria I, Jashemski, W. F., 1995, fig. 11)

Dates

5th century CE

Bibliography

- Alexander, M. A., Ben Abed-Ben Khader, A. and David, S., Corpus des Mosaïques de Tunisie, Thuburbo Majus, Les mosaïques de la région Est, V. II, fasc.4, INA, Tunis, 1994, pp.39-66, Pl. XXIV. (worldcat)

- Ben, Abed-Ben Khader, A., Corpus des Mosaïques de Tunisie, Thuburbo Majus, Les mosaïques de la région Ouest, V. II, fasc.3, INA, Tunis, 1987.(worldcat)

- Bullo, S., Ghedini, F., Amplissimae atque ornatissimae domus: l’edilizia residenziale nelle città della Tunisia romana, Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 2003, pp.214-217. (worldcat)

- Jashemski, W. F., "Roman Gardens in Tunisia: Preliminary Excavations in the House of Bacchus and Ariadne and in the East Temple at Thuburbo Maius," AJA 99 (1995), pp. 559-576. (worldcat)

- Jashemski, W. F., “Ancient Roman gardens in Campania and Tunisia: a comparison of the evidence,” Journal of Garden History, 16/4,1996, pp. 231-243.(worldcat)

- Jashemski, W. F., "The Courtyard Garden in the House of Bacchus and Ariadne at Thuburbo Maius, Zaghouan, Tunisia" in Sourcebook for Garden Archaeology, Mthods, Techniques, Interpretations and Field examples, ed., A-A Malek, Berne, Suisse, Peter Lang, 2013, coll. Parcs et Jardins (Peter Lang/Fondations des parcs et jardins de France), pp. 595-601.(worldcat)

- Lantier, R., "Un bassin a mosaiques de Thurburbo Majus", BAC 1944, pp. 280-82 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- Malek, A.-A., "Le jardin au fil de l’eau : mises en scène paysagères dans les domus de Maghreb antique", in L’eau dans les villes du Maghreb et leur territoire à l’époque romaine, Brouquier-Reddé, V., Hurlet, F. (dir.), Bordeaux, Ausonius, 2018, pp. 235-254. (worldcat)

Pleiades_ID

TGN ID

Contributor

Publication Date

21 Apr 2021