Porticus of Pompey

Province

Italia

Italia (Pleiades)

Italia, Regio I (Pleiades)

Location

Sublocation

Region IX Circus Flaminius

Campus Martius (Pleiades)

Garden

Garden of the Porticus of Pompey

Porticus Pompei (Pleiades)

Keywords

- cavea

- colonnade

- curia

- fountain

- latrine

- museum

- nemus (grove)

- porticoes

- quadriporticus

- scaenae frons

- statue

- temple

- theater

- viridarium

Garden Description

Completed in 55 BCE on the Campus Martius, the Porticus Pompeianae, or Porticus of Pompey, was Rome’s first public park (Plin. HN 37.6.13; Propertius 2.32.11 | Trans.; Vitruvius De Arch. 5.9.1). Funded by the eastern victories of the general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, the Porticus comprised a double nemus, enclosed by a quadriporticus, and a curia. The western end of the precinct featured his theater-temple complex. The Pompeium Theatrum was the first permanent stone theater constructed in Rome; its cavea served as the steps to Pompey’s victory temple, dedicated to his protector, Venus Victrix.

Caesar was murdered in the Porticus on March 15, 44 BCE at the foot of the statue of his rival in front of the Curia Pompeia (Cicero Div. 2.23; Suetonius Iul. 88; Plutarch Caes. 66). The Porticus is known primarily from the Severan Marble Plan (FUR) and ancient sources, but archaeological evidence for ancient garden levels was discovered during work under the Teatro Argentina in 1968-9. The only archaeological remains of the Porticus currently visible are the back of the Curia and the adjacent latrines just to the west of the Republican temples of L’Area Sacra di Largo Argentina.

Vitruvius noted that a porticus was often attached to a theater, as in the case of the Porticus Pompeianae, to shade the audience from rain (De Arch. 5.9.1) and that the planted open space (virid[i]aria) of the porticus provided health-benefits, particularly in clearing the eyes (De Arch. 5.9.5).

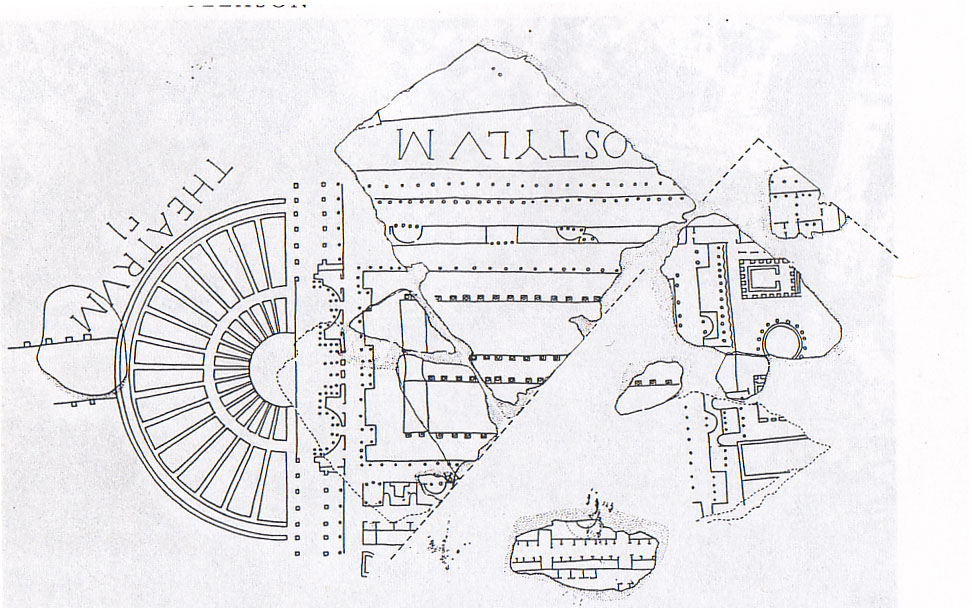

The Marble Plan and Renaissance drawings of the FUR depicted the quadriporticus (180 x 135 m.) as aligned along an east-west axis (Fig. 1). The archaeological evidence suggests that the two elongated rectangles on the Marble Plan depict Martial’s nemus duplex, a double sacred grove, in the center of the Porticus (Mart. 2.14.10 | Trans.). Excavations of the Teatro Argentina in 1960s revealed garden soils in the center of the Porticus for the initial Pompeian phase and the Augustan rebuilding phase of the garden. Later phases were not preserved. Epigraphic evidence has led to the common restoration of two interior porticus, which may have replaced the nemus design in one of the many re-buildings of the complex (discussed below).

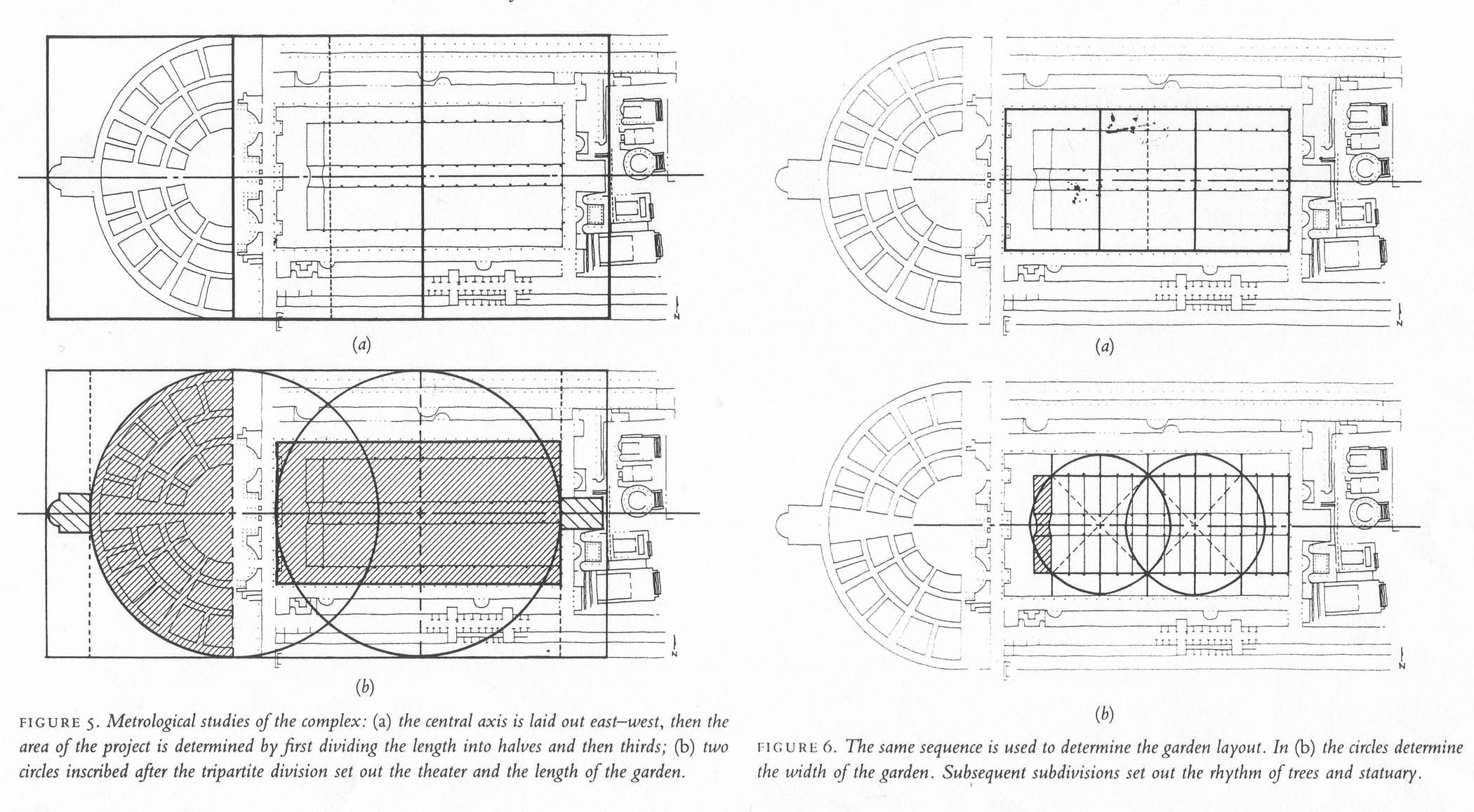

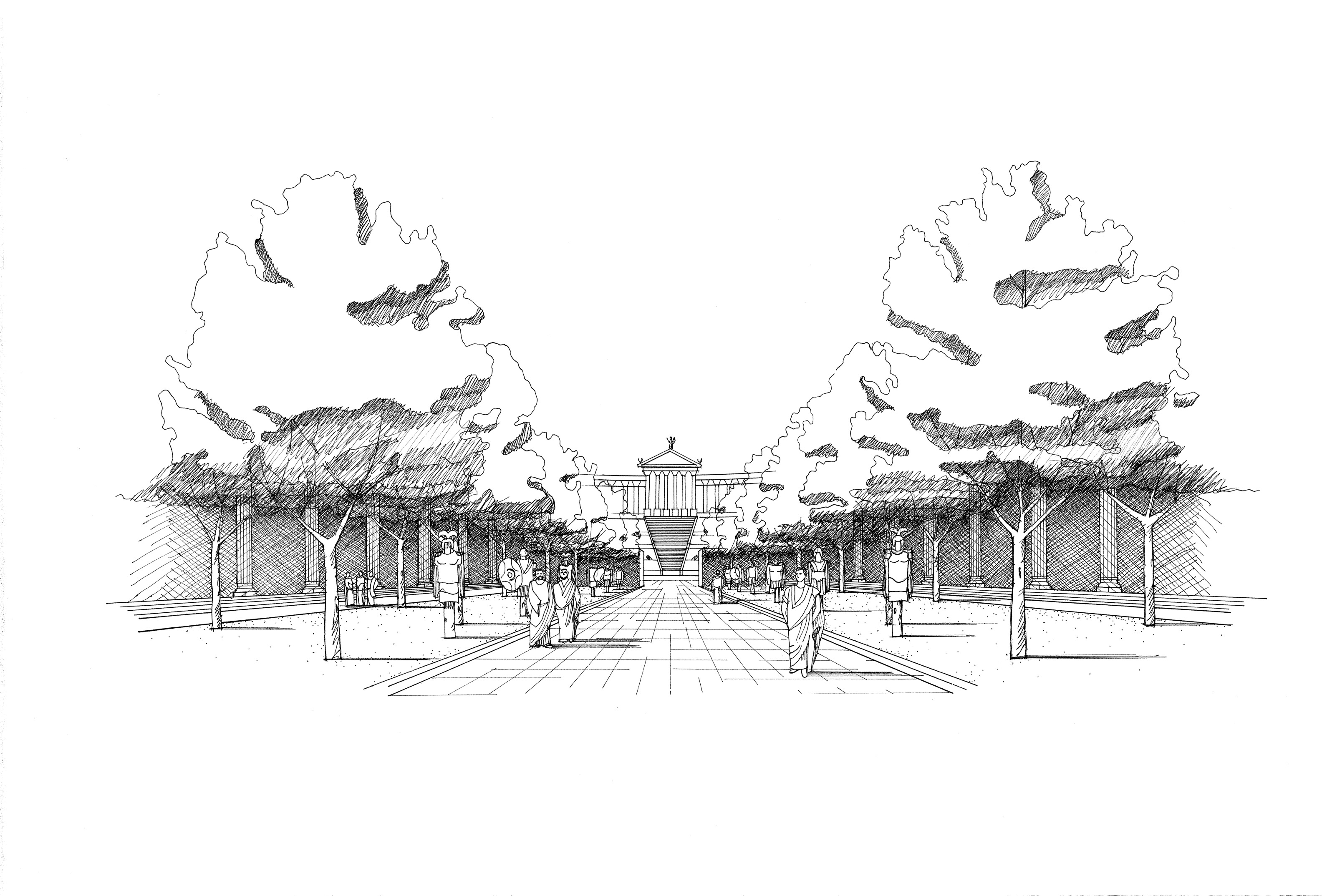

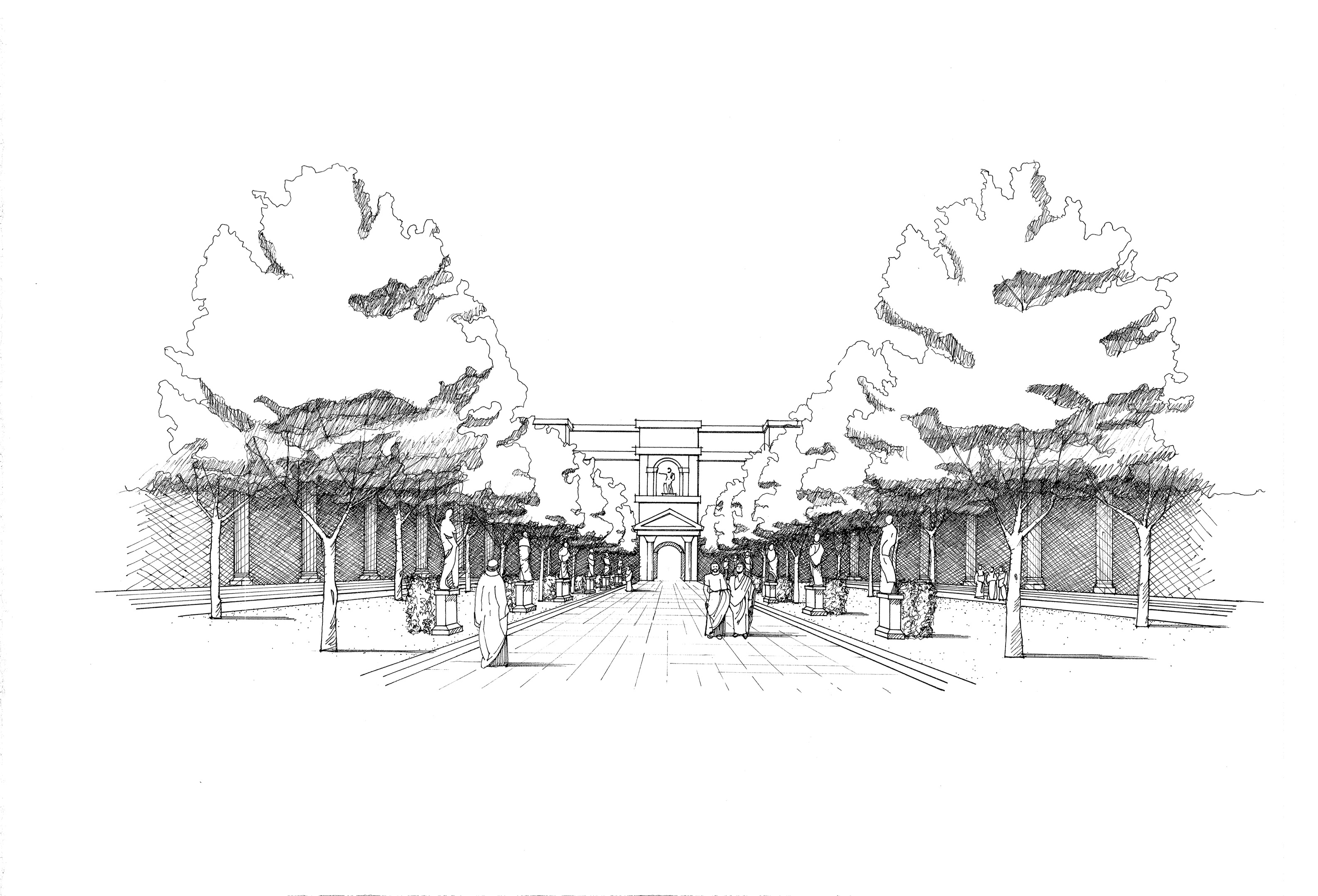

The porticus and the garden (virid[i]aria) were designed on the basis of symmetry and proportion, which Vitruvius set out thirty years later. Metrological studies of the garden and architecture demonstrated that the garden was designed symmetrically along a central axis (975 Roman feet) and divided into three smaller rectangles of the harmonious proportions and three overlapping circles of equal size in conjunction with the design of the porticus, the theater, and the temple (Fig. 2). On the basis of these analyses, K. L. Gleason argued that the Theater featured a temporary scaenae frons in its original phase, allowing a strong visual relationship between the porticus, theater, and temple (Fig. 3). M. Gagliardo and J. Packer have proposed that the theater had a permanent scaenae frons from the inception of the complex, blocking the powerful line of sight from the porticus towards the Temple of Venus (Fig. 4). Certainly, the scaenae frons was erected during the radical remodeling of the complex by Augustus in 32 BCE to downplay the political overtones of Pompey’s complex (Suet. Aug. 31), as he also transformed the Curia into a latrine (Cassius Dio 47.19.1 | Trans.).

The nemus, dedicated to Venus Victrix, was planted with evenly spaced ranks of plane trees (Platanus orientalis) (Pliny HN 35.39; Propertius, 2.32.11-12). Other plants may have included the myrtle (Myrtus communis), associated with fertility and Venus, and laurel (Laurus nobilis), the symbol of victory, as suggested by P. Grimal. The plane trees lined the central avenue, directing the visitor’s view west to the Theater/Temple of Venus. The lay-out of the double nemus and the controlled views of it established a relationship in architecture and greenery between Pompey and Venus.

The double nemus also contained foundations and numerous works of art. Fountains were also present in the Porticus, probably in the nemus duplex (Propertius, 2.32.11-12), but their exact location is unknown. Set within the garden and colonnade of the Porticus Pompeianae, as well as the theater, was an extensive assemblage of art (Cicero ad Att. 4.9.1 | Trans.). The ideologically specific collection of art celebrated Pompey’s victories and eastern culture. The Roman sculptor Coponius crafted female representations of the fourteen eastern nations that Pompey had defeated, which were located circa Pompeium- probably in the nemus (Pliny HN 36.41). A painting of Alexander the Great by Nicias also had a special place with the complex.

Greek art and sculpture (often with Greek inscriptions) and golden Pergamene curtains were situated in the colonnades of the Porticus. This garden museum displayed manubiae, the booty from Pompey’s victories, while the Temple to Venus served as a physical reminder of Pompey’s eastern victories and his status as Venus’s favored general. Scholars debate whether Pompey was trying to evoke or copy a Hellenistic form of monarchy through his display of eastern art; F. Coarelli has argued against such an interpretation, while A. Kuttner has argued in favor. In contrast to the splendor of the rest of the precinct, Pompey’s own residence, which was attached to the complex, was notably modest-“like a dingy to a ship.

The Porticus Pompeianae not only functioned as a victory monument and political space, but it was a valued amenity for the people of Rome, where men and women came to meet their lovers or seek new ones (Propertius 2.32.30; Catullus 55.6; Ovid Ars Am. 1.67, 11.1.11, 11.47.3).

Augustus’ remodeling of the theater and porticus (in 32 BCE), discussed above, minimized the political nature of the space and instead emphasized the porticus as a space of pleasure. After a fire in 80 CE, Domitian restored the complex. It also burned during the reign of Carinus (283–85 CE) and was restored by Diocletian.

Figures

Fig. 1. Restored plan of the Porticus Pompeianae based on the Marble Plan, the archaeological remains of the Republic temples, and the foundations of the theater. Gleason, 1994, p.16.

Fig. 2. Metrological studies of the porticus: the porticus, the theater, and the garden were laid out using a complex understanding of geometry. Gleason, 1994, p. 18.

Fig. 3. Perspective along the central axis from the Curia to the Temple of Venus Victrix atop the theater in the original phase. © Lori Cockerham Catalano.

Fig. 4. The view along the central axis from the Curia to the Temple of Venus Victrix atop the theater after the erection of a permanent stage building by Augustus; the unity of the space is lost due to the erection of the scaenae. The temple cannot be seen at all. © Lori Cockerham Catalano.

Dates

55 BCE

Bibliography

- F. Coarelli, Il Campo Marzio, Rome, 1997, pp. 539-79. (worldcat)

- P.A., Gianfrotta, O. Mazzucato, M., Polia, “Scavo nell’area del Teatro Argentina 1968-69,” Bollettino della Commissione Archaeologica Comunale di Roma 81 (1968-69), pp. 25-36. (worldcat)

- K. Gleason, “Porticus Pompeiana: a new perspective on the first public park of ancient Rome,” Journal of Garden History Vol. 14, No. 1 (1994), pp. 13-27. (worldcat)

- K. Gleason, “Gardens and Landscapes of the Past,” University Expeditions, Vol. 32, No. 2 (1990), pp. 3-13. (Expedition)

- P. Grimal, Les Jardins Romains, Paris, 1969, pp. 171-6. (worldcat)

- E.M. Steinby (ed.), Lexicon topographicum urbis Romae, s.v. "Porticus Pompei" (P. Gros), pp. 148-9. (worldcat)

- A. Kuttner, “Culture and History at Pompey’s Museum,” Transactions of the American Philological Association 129 (1999), pp. 343-73. (worldcat)

- M. Gagliardo and J.Packer “A New Look at Pompey’s Theater: History, Documentation, and Recent Excavation,” American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 110, No. 1 (January 2006), pp. 93–122. (worldcat)

- E. Macaulay-Lewis, “Use and Reception,” in A Cultural History of Gardens in Antiquity, ed. K.L. Gleason, London, 2013, pp. 99–118. (worldcat)

Pleiades ID

Contributors

ORCID

E.R. Macaulay (0000-0002-4551-7631)

Kathryn Gleason (0000-0001-6260-8378)

Publication date

17 April 2021